What About the Men

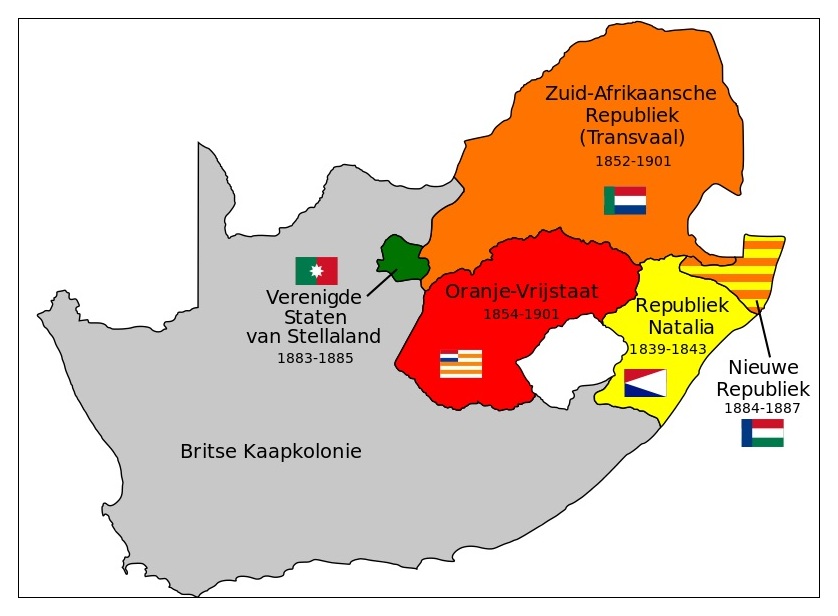

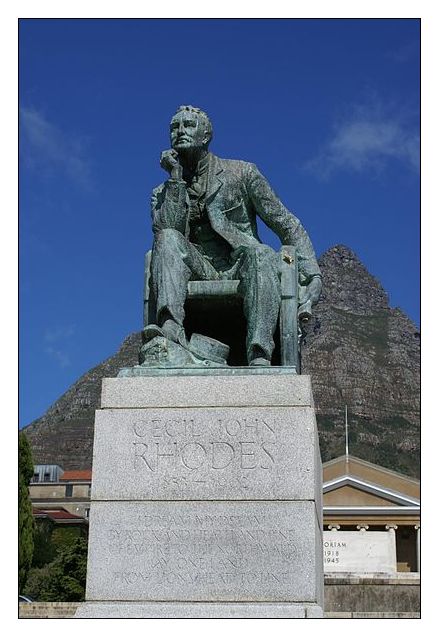

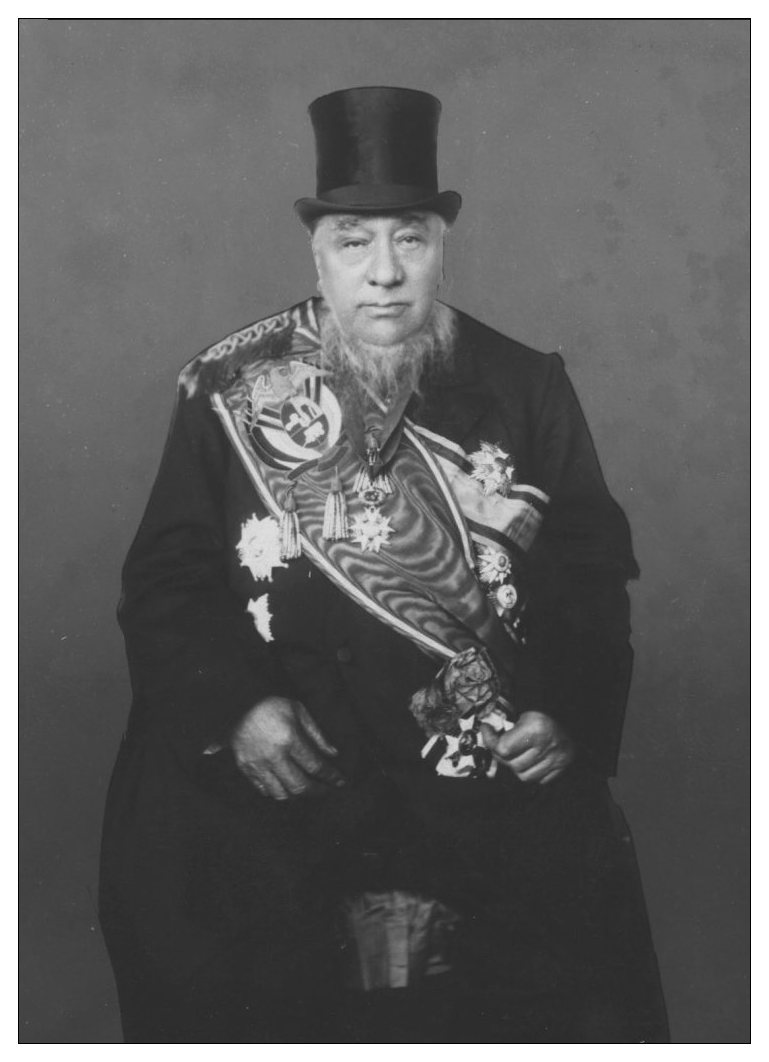

The Lampens and Heysteks had no idea of the volcanic eruption of wars that would follow in the next century after their President Kruger decided to resist Britain’s land grab for the second time in twenty years. Most Boere believed the success of winning the First Anglo-Boer War would be repeated in a few months’ time. Could they have foreseen that half the world would descend on our tiny corner of Africa in a mad explosion of armies and volunteers? Some came to defend the largest and most glorious of the world empires of that era, others jumped to the aid of the Zuid Afrikaansche Republiek and its handful of Bible-clutching farmers being swallowed up by the greed of men like British politician/entrepeneur Cecil John Rhodes, and his fellow imperialist Lord Alfred Milner who said he was going to “break the power of Afrikanerdom”. After meeting Milner five months before the war broke out, Jan Smuts discerned that Milner would actually be “more dangerous than Rhodes”. Rhodes had already made his life calling clear way back in 1877: “Why should we not form a secret society with but one object the furtherance of the British Empire and the bringing of the whole uncivilised world under British rule for the recovery of the United States for the making the Anglo-Saxon race but one Empire.” – he had quite a beef with the U.S.’s independence from England. Concerning Africa, Rhodes had famously envisioned a continuous “red line” of British dominions from Cape to Cairo, declaring “..if there be a God, I think that what he would like me to do is paint as much of the map of Africa British Red as possible…”

While searching for any Boer War or P.O.W. records about the Lampens and Heysteks, I stumbled onto some interesting bits of information that must have colored their lives during this time. Actually, the interesting bits grew into such an overwhelming find of books, articles and dissertations that I almost wanted to give up writing anything. The recent centenial commemorations of the Boer War stirred up a beehive of writers reviewing one argument after another in the flashpoint that South Africa has been this past century, starting with the Boer War. When I complained about this to Cara, “the past is not a record of events, it is an argument”. Maybe I should just mention the P.OW. records, right? But so much swirled into the atmosphere of Oupa & the family’s lives, how can I not mention a few?

I followed three trails surrounding, in particular, the men in our family during the Second Boer War: The first trail revealed that our “Oom Herman Lampen” (Oupa Wijtse’s boetie and Gerhard, your 2x great-oupa) fought for the Boere in the “Belgium and Dutch Volunteer Forces”. Hmm, interesting. Prying a bit more, I found there was actually a whole host of foreign nationals who jumped into this warring cauldron on the Boer side. Crazy people, seriously, why would you do that? (Oefff… loaded question.).

The second trail opened up as I looked at the scope of this seemingly-forgotten little war and discovered the most interesting people from all over the world assembling on the stage of what was actually the largest and costliest of the wars waged by Britain since the Napoleonic Wars, and before WWI (nearly half a million British forces fought against 88,000 Boer forces). I want to yell at my history school teachers, “ag, you could have made it so much more interesting!”

The third trail clued me in about one of Ouma Hannie and Oupa Wijtse’s little ones that they lost in the concentration camp, a boy named Hendrik DE LA REY Lampen. Sheesh, grandparents, why saddle the infant with that name?

First trail: the records on foreigners fighting for the Boere revealed men from America, Ireland, Austria, Bosnia, Bulgaria, Germany, Greece, Spain, Switzerland, Sweden, Denmark and Norway, and even Brazilians and one brave chap from Chili. Ja, Chili. The continent of Africa was already mostly carved up into colonies belonging to competing empires, and some of these internationals certainly jumped on the bandwagon for the Boere with strong anti-imperialist feelings, but others just had a huge beef with Britian even if they could not officially support the Boere for various political considerations, or because of family connections through the long British royal family lineage—Germany and Russia in particular. Scarcely twelve years later “The Great War to end all wars”, WWI, would break out. One wonders how the Second Boer War added to the tensions brewing in Europe, or was it an unintended dress rehearsal in small?

The known total of these volunteers was 2,825. Some were everyday-townsmen or mariners turned-goldrush adventurers working on the Johannesburg mines with hardly any skills for warfare in the veld. Many of the six hundred Belgians and Dutch were already living in the country, actually. Other international volunteers were professional soldiers, a few actually rising to some prominence in our commandos, such as the French General Comte de Villebois-Mareuil, the Russian Colonel Maximov, the German Captain von Weiss. Some foreigners served as ambulance workers, including the Tsar of Russia’s units and a Scandinavian unit.

Second trail: a few interesting people showed up everywhere—some we probably remember vaguely, but others were a bit of a surprise to find. Volunteers for the British Empire included citizens of the Commonwealth nations of Canada, New Zealand, Tasmania, and Australia, of course. Indians served too, most famously Mahatma Gandhi, who was a stretcher-bearer in the volunteer Indian Ambulance Corps. Most British subjects felt it was their duty to fight for “King and Country” (Queen Victoria died in January 1901), although England was rife with outspoken socialist and pacifist opponents of the war. Emily Hobhouse was probably the most famous of these, visiting the concentration camps in South Africa and subsequently wielding a powerful influence on British politics.

But look here: another medic who wrote quite a few books on the Boer War, including our Rustenburg contingent in some of his stories, was “Sherlock Holmes”s famous author—and actually a medical doctor—Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. He was knighted after his article, “The War in South Africa: Its Causes and Conduct”, written in defense of the Brits’ conduct in SA, came out in 1902. So, obviously he was going to write totally pro-British, right? Doyle actually had something good to say about the Rustenburgers: they were “…brave, hardy and fired with a strong religious enthusiasm. Mounted on their hardy little ponies, they possessed a mobility which practically doubled their numbers and made it an impossibility to ever outflank them. As marksmen they were supreme.” Howzat! Maybe my small accomplishments in target shooting came from Oupa or one of our Heystek-Erasmus-Malan forebears, nê? Of course, I am not riding wild on a pony… Doyle also remarked, “They were all of the seventeenth century, except their rifle.” (Kruger’s government had obtained the best of weapons from a very pro-Boer Germany in preparation for the war, including 115mm Creusot field guns (Long Toms), and the Mauser, an excellent rifle for shooting long range.)

And then there were the hordes of reporters on both sides—including Britain’s Winston Churchill, who famously got captured by the Boere and escaped—we all know about him, right? But the surprise find here was that young Winston’s aunt, the “elegant Lady Spencer-Churchill”, became the first woman war correspondent in 1899 and wrote for the Daily Mail from behind the Boer siege line in Mafeking. And then apparently a few wealthy British blokes also arrived under the pretense of reporting, enjoying a bit of “adventure” witnessing action on the front-lines of their empire.

And then there were the hordes of reporters on both sides—including Britain’s Winston Churchill, who famously got captured by the Boere and escaped—we all know about him, right? But the surprise find here was that young Winston’s aunt, the “elegant Lady Spencer-Churchill”, became the first woman war correspondent in 1899 and wrote for the Daily Mail from behind the Boer siege line in Mafeking. And then apparently a few wealthy British blokes also arrived under the pretense of reporting, enjoying a bit of “adventure” witnessing action on the front-lines of their empire.

Now add to this brew the rest of the syndicated media developing its first sensation of power and manipulation in reporting on this conflict (remember the Derdepoort Massacres story spreading in Germany?), as well as the telegraph playing an operational role for the first time right here in South Africa, and you have an explosion of global popular sentiment in ways no one could have foreseen. Since the Jameson Raid the world was watching this little corner in Africa with baited breath, it seems. The Scandinavian volunteers arrived in Pretoria in August 1899, two months before Pres. Kruger decided to issue his ultimatum to the Brits and war was declared. Then Mafeking was besieged by the Boere, including so many “undisciplined, independent and stubborn” Rustenburgers… Mafeking became the match to the fire of the British populist media. News of the siege by the Boere, and the almost-mythically heroic Col. Baden-Powell, including the elegant journalist Lady Sarah Spencer-Churchill, braving it out under dire circumstances in this town, swept people in Britain, Canada and Australia up into a frenzy of pro-British sentiment. When the siege was broken in May 1900, wild celebrations broke out all over the empire, including in London’s Piccadilly Circus, where a new word was coined: “mafficking”, meaning “wild rejoicing”. (I have never heard that word.) Even three decades later the hype of these celebrations were depicted in the Shirley Temple movie, A Little Princess (based on Frances Hodgson Burnett’s 1905 novel,) in a scene with little girls and teachers rushing out into the London streets to celebrate, “Mafeking is relieved!”

The relief of Mafeking by British reinforcements nearly ended the war for the disheartened Rustenburgers that May, had it not been for Z.A.R. State Attorney Jan Smuts and Gen. Koos de la Rey’s role in getting the Rustenburgers up and fighting again by July (see “That Blêddie Spider” on June 8). But in stark contrast to the “June gloom” over this dorpie, what followed in July 1900 through the rest of the war was to become the stuff of legend…

Initially the foreign legions fighting for the Z.A.R. functioned independantly. However, after the French Legion under Villebois-Mareuil met with a major disaster at Boshof in the Free State, Gen. de la Rey was placed in command of all foreigners—the same de la Rey that Oupa Wjitse, Oom Herman and all the other Heystek-family men fought under.

Initially the foreign legions fighting for the Z.A.R. functioned independantly. However, after the French Legion under Villebois-Mareuil met with a major disaster at Boshof in the Free State, Gen. de la Rey was placed in command of all foreigners—the same de la Rey that Oupa Wjitse, Oom Herman and all the other Heystek-family men fought under.

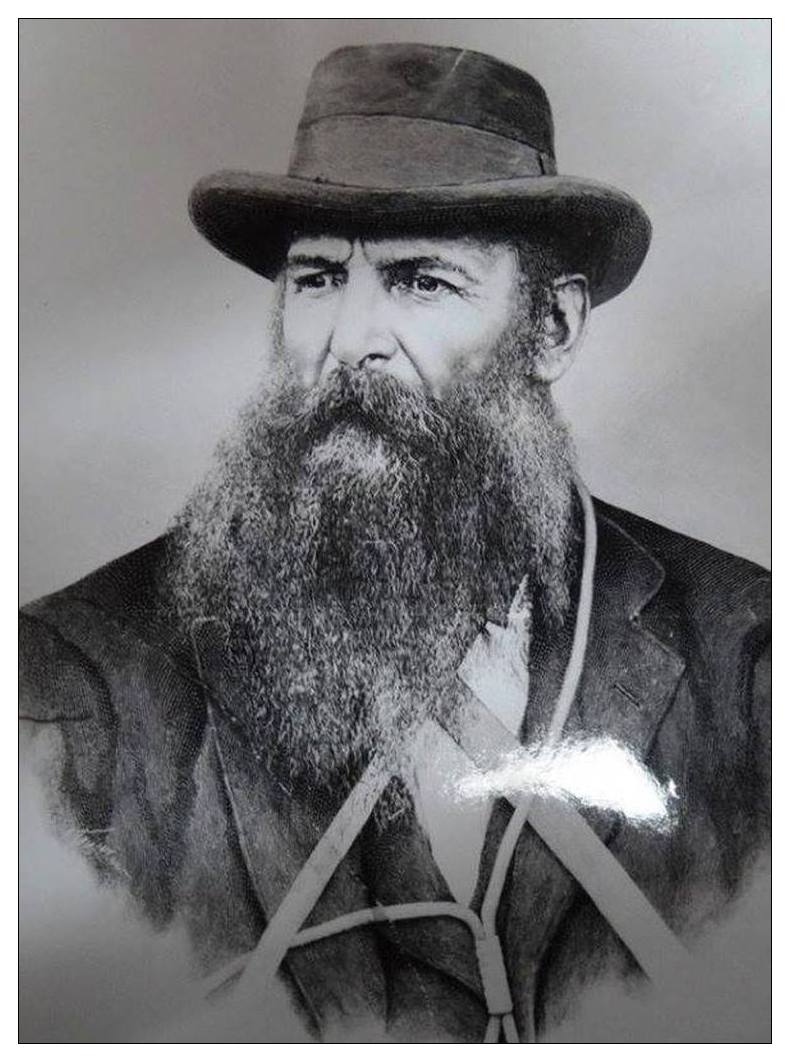

Which all leads to my third trail: a few descriptions of the character of Koos de la Rey that may possibly give us an idea of the kind of man who commanded our men in the war, how he shaped their war experiences, and why those who did not get captured fought until the bitter end. It might explain, maybe, why Oupa and Ouma named their youngest baby Hendrik de la Rey Lampen in November 1900.

Even though he was a fanatic in his support for the Boer cause, Gen. de la Rey fervantly did not want to go to war, as he believed the Boer republics were not ready. Pres. Kruger accused him of cowardice during a Volksraad session just before war was declared, to which De la Rey replied, “I shall do my duty as the Raad decides, and you will see me in the field fighting for our independence, long after you and your party have fled the country.” Which became true in a way. Pres. Kruger went into exile in May 1900 and died in Switzerland in 1904, while de la Rey fought until the “bitter einde” of the war. At the war’s start, De la Rey had argued against besieging Mafeking, but ultimately accepted a commision and fired the first shot of the Boer War during a skirmish to derail an armoured train en route from Mafeking to Kimberley. After five hours the Brits surrendered.

As was typical throughout the war, though, the Boere often had no way of taking care of their prisoners and would let them go again. These were mostly farmers who were called up to fight in a commando for a week or so, relying on their own provisions and horses. Gen. de la Rey was particularly well known for his care of British captives and especially of the wounded. (The Brits took care of the Boer wounded too—often times the Boere would surrender their own wounded to the English for medical care, since the Boere had no medical units in the field. However, the Boer prisoners were then sent to P.OW camps, of course.) Conan Doyle also commented on this characteristic: “…on reaching the Jagd Drift it was found that the fighting was over and that the field was in possession of the Boers. De la Rey was seen in person…it is pleasant to add that he made himself conspicuous by his humanity to the wounded.”

Koos de la Rey and his wife’s family consisted of twelve children and six orphans they had taken into their care. If you wanted to see the true “Bible-clutching Boer”, General Koos was your model. A modestly educated man and sincere believer in God, de la Rey had a pocket-Bible that never left his person according to those close to him. Apparently quite influential on de la Rey was also a controversial chap known as “Siener van Rensburg” (a seer), who had prophetic-type visions with such accuracy that they escaped many a trap or point of capture in battle. De la Rey considered him to be a prophet of God.

Koos de la Rey and his wife’s family consisted of twelve children and six orphans they had taken into their care. If you wanted to see the true “Bible-clutching Boer”, General Koos was your model. A modestly educated man and sincere believer in God, de la Rey had a pocket-Bible that never left his person according to those close to him. Apparently quite influential on de la Rey was also a controversial chap known as “Siener van Rensburg” (a seer), who had prophetic-type visions with such accuracy that they escaped many a trap or point of capture in battle. De la Rey considered him to be a prophet of God.

Throughout the war Koos de la Rey became known as the Lion of the West; the Scourge of the English; King of the Magaliesberg (which was known as “De la Rey’s country”). His influence on his men (and consequently on our family) is well summarized in Gen. Jan Smuts’s post-war description of him and his “little army, especially the Rustenburg part”. Smuts believed it was De la Rey’s principles of constant practice and hard work that formed his men into such a tough commando, and also his “indomitable nature which would never leave the enemy alone, even when he could not be effectively dealt with… [that] polished them into that splendid body of men to whom in the later stage of war it was almost impossible to set too hard a task either of physical endurance or heroic attack.”

I keep on picturing Oupa, Herman, Daniel Heystek (Ouma’s brother), and other family members in these descriptions. Is this how they lived? Did the person of, and the leader in Koos de la Rey so inspire them in this cause that those who did not get captured and sent away to India or Bermuda chose to fight to the bitter, so very bitter end? If Oupa was part of the Siege of Mafeking, he would have known de la Rey for a year by the time his son was born in 1900, and perhaps this is why he convinced Ouma of the name Hendrik de la Rey Lampen.

So much more can be expounded on. Probably the best book to read with regards to the Rustenburg Commando’s military details would be Wulfsohn’s book on Rustenburg at War. The war finally ended with the signing of the Treaty of Vereeniging on 31 May, 1902. Gen. de la Rey was instrumental in negotiatons with Lord Kitchener a couple of months before the treaty signing, and traveled to Europe with Generals de Wet and Botha after the war to raise funds for the impoverished Boer families on their burnt-out farms. In 1903 de la Rey made his way to India and Ceylon (Sri Lanka) to convince the remaining prisoners of war to sign the oath of allegiance to England, so that they could return to their families.

Prisoners of War:

By June 1901 Ouma Hannie was already in a concentration camp somewhere, her three youngest had died, and her sister Emmie, Herman Lampen’s wife Goosje and a few other women had been living on the Wysfontein farm for a few months after the Kakies left them alone in agreement with the Boere at the end of November 1900 (see the previous Concentrated Death I & II posts). The timing points to the two Lampen brothers (Oupa Wjitse and Herman), and Oupa’s Heystek brothers-in-law arriving at the nearby Steenbokfontein farm (Ouma’s younger brother, Jan Heystek’s farm) earlier in June, possibly to gather provisions. Here Jan took ill with a “stomach fever” and was subsequently taken to the Wysfontein farm where Goosje, Emmie, and a few more family women could take care of him. The men left again as there was a whole lot of Kakie activity in the area. Sadly, Jan died on June 10. Struggling, the grief-stricken women managed to construct his coffin by hand. Oupa Wijtse and two others arrived just in time to dig a grave and help with Jan’s burial. Other Boere helped stand guard in the hills while the rest of Gen. de la Rey’s commando was following a Kakie laager. By the 17th of June, Herman and a few others had returned to the vicinity of the first farm, Steenbokfontein, and Herman is recorded as having been taken captive here. Somehow Oupa was not with Herman on the 17th, for he fought until the “bitter end” with de la Rey. Herman was sent to Amritsar in the Punjab, India, a mainly-Sihk area, where prisoners were housed in the Gobindgarh Fort. Goosje, and their little boy, Geert, were held captive in the Mafeking concentration camp with Emmie, Ousus and Nakkie, the other Heystek sisters.

According to the Anglo Boer War Museum, four of the Heystek and fourteen Malan men were captured and sent to P.O.W. camps in Bermuda, Diyatalawa on Ceylon (Now Sri Lanka). Ouma Hannie’s father, Jan, was kept under house arrest in Pretoria, while two of his brothers, Joost and Hendrik Heystek, were sent to Shahjahanpur in India, and Diyatalaw in Ceylon. Joost was 54, and Hendrik was 50 years old.

Other sources:

https://www.britannica.com/event/South-African-War

http://www.fofweb.com/Electronic_Images/Maps/HMOF4-12-c.pdf

https://www.angloboerwar.com/…/1465-hillegas-chapter-9-fore…

http://samilitaryhistory.org/vol112db.html

http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/cecil-john-rhodes

http://pages.uoregon.edu/kimball/Rhodes-Confession.htm

https://independentaustralia.net/…/the-boer-war-beginning-o…

http://www.sahistory.org.za/…/winston-churchill-captured-bo…

http://www.branchcollective.org/…

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_South_Africa_Company

https://streamsandforests.wordpress.com/…/rustenburg-comma…/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siener_van_Rensburg

http://www.wmbr.org.za

Previously published on: https://www.facebook.com/groups/Lampens/