The Second Anglo Boer War ended in May 1902. World War I—The Great War, the War to End All Wars—erupted twelve years later on July 28, 1914. While writing the story “What About the Men” in the Second Anglo Boer War (post # 23A), I was struck by so many nations descending upon our little corner in Africa, itching to fight on either the side of Great Britain or the Boere. It looked like a dress rehearsal for the next war that would tilt the world into the “bloodiest century in modern history.” (Stephen Elliot, The Most Violent Century).

But who really remembers the First World War nowadays? I vaguely remember old men marching with red poppies in their lapels some time during my childhood, but my family never really talked about this “English war.” Then in 2011 came Steven Spielberg’s amazing movie, War Horse, to wake up the older folks and introduce younger generations to WWI. And now, in 2018, red poppies are seen all over the news and other media (see British Legion Story of the Poppy in Resources, and my friend Inge’s beautiful poppy painting), reminding us that on November 11 at 11 A.M., one hundred years ago, the world shuddered itself out of nine million soldier- and seven million civilian wardeaths. And then death marched on with another 50-100 million dead in the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918. Unimaginable to us today.

WWI’s history touches my own family on two fronts: my husband’s maternal grandfather, Robert Coxhead, served in the British Navy. He experiencing his share of hostilities on the navy monitor HMS Marshall Soult during shelling operations against German positions along the Flanders (Belgium) coastline.

And then on the other side of the world, our Ouma Hannie Lampen assisted German internees in a camp on Roberts’ Heights outside Pretoria. Nobody can remember why, or what the story was behind her British Marshall Law pass, keeping its silent testimony of this forgotten era in our Lampen archives.

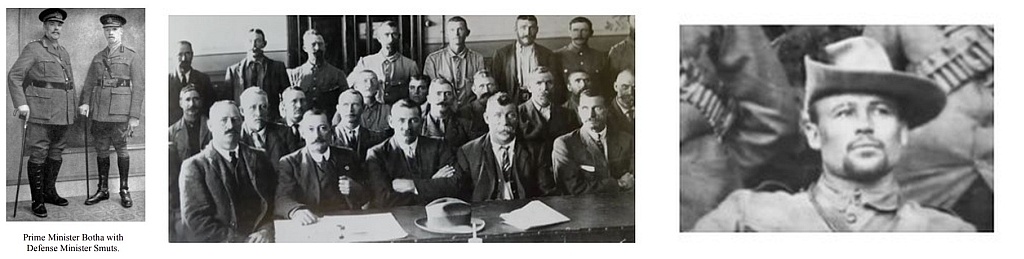

We know that, having survived the most brutal traumas of the Boer War just twelve years prior to WWI, our W.S. Lampen family were now rebuilding their lives in the city of Pretoria. After the three youngest children’s concentration camp-related deaths in 1901, four more children had been born: Kieka in 1903, Mientjie in 1905, my mother Anneke in 1911 and Herman in 1913. After the Boer War our old nemesis, the English Lord Milner, and his “Kindergarten” lackies were in full control of the four South African colonies. In 1905, after Milner’s term of office expired, two young Boer leaders, Jan Smuts—who had once fought under “bittereinder” General Koos de la Rey—and General Louis Botha, negotiated successfully in London for the Transvaal colony’s self-government. (Smuts had graduated law at Cambridge with a double-first in 1894.) Smuts now worked towards the union of all of four Southern African colonies, drafting a constitution which was eventually ratified by all four colonies, passed by the British Parliament and given the “Royal Assent” by King Edward VII in December 1909. In 1910 the self-governing Union of South Africa came into being, with Louis Botha as the Prime Minister, and Jan Smuts as his deputy. Both men now served on the Executive Council in the name of the British Crown. (Both Botha and Smuts are also part of our family line, by the way.) Representing the British Monarch in South Africa for the next thirty-odd years would be a line of royals, starting with Viscount Gladstone.

Political schisms among the Afrikaners through the next few years caused a deep divide between the older Boer generals Hertzog, Steyn and de Wet who wanted all ‘foreign’ influences to be purged, and the formidable younger duo, Prime Minister Botha and Defense Minister Smuts, who were willing to commit South Africa to supporting British interests. When the government joined the Allies at the outbreak of WWI and sent South African troops to invade the next-door colony German South West Africa upon the British government’s request—as we say in Afrikaans—”die gort was gaar.” (The fat was in the fire.) Even the English heroine, Emily Hobhouse, who fervently protested the British government’s actions in the Boer War concentration camps (and who may have even met some of our Heystek family during her visit to the Mafeking Concentration Camp in April of 1901), pleaded unsuccessfully with her friend Jan Smuts in a letter on August 8, 1914, “Dear Oom Jannie, The Crash has come and Europe is armed to the teeth—an Armageddon indeed. Our wretched Imperialists have… drawn us into a war which will ruin England also… For pity’s sake don’t let South Africa be dragged in. You have Germans, poor dears, on your flank … the war is spread already wide enough. Cruel and wicked! And paralysing in the stupendous character it has assumed. None can foresee the end.“

The invasion, however, was launched in early September, 1914. Several of the “Old Boer” leaders serving in the South African government, including Brigadier-General Beyers, Generals de Wet and Oupa’s hero, Gen. Koos de la Rey, resigned their commissions with the Union Defense Force on September 15. Beyers wrote, “It is sad that the war is being waged against the ‘barbarism’ of the Germans. We have forgiven but not forgotten all the barbarities committed in our own country during the South African [Boer]War.” While Gen. de la Rey was a supporter of Louis Botha, he had advocated against joining the war unless South Africa got attacked. De la Rey tried to keep the peace between the two factions, but his untimely death while driving through a gang-related police blockade on Sept, 15, convinced many angry Boere that their hero had been assassinated by the government. A few thousand Afrikaners joined these leaders in the Afrikaner “Rebellie” that erupted, resulting in Jan Smuts declaring Martial Law on October 11. The rebels saw the government’s actions as a betrayal of their sacrifices in the Boer War and, even more so, a betrayal against their German friends who had supported them against Britain during the Boer War. Many Afrikaners also have strong German roots, not the least of them our Oupa Wijtse Sijger Lampen, whose father Geert Lampen had immigrated to the Netherlands from Hesepe in the Lower Saxony district. These family ties were very strong—Oupa’s cousin Janna Lampen in Hesepe was still still corresponded with the South African Lampens as well, so I can imagine how strong the emotions must have run in our family.

We have a Martial Law permit issued to and signed by Oupa W.S. Lampen on 26 November, 1914—pretty much in the middle of the Rebellie—by the Assistant Commandant of the South African Police in Pretoria. Unfortunately we do not know what this was about. Most of the handwriting is in pencil and did not last well through the past hundred years or so. Did Oupa visit a Boer rebel prisoner in the Pretoria jail?

Two of the Boere rebels, Lt. Col. Manie Maritz and Captain Jopie Fourie, did not resign their Active Citizens Force officer’s commissions. Still officially part of the Union Forces, Jopie Fourie’s rebel commando was responsible for 40% of casualties among the Union Defense Forces during the “Rebellie.” Captured on 16 December 1914 in the Rustenburg area and court-martialed for treason, despite a petition for leniency brought to Smuts by a delegation of Afrikaner leaders, Jopie was executed four days later by firing squad at the Pretoria Jail in Potgieter Street, apparently close enough to our Lampen family’s home for the shots to be heard. I remember my mother, Anneke, telling me about Ouma Hannie’s anguished response to hearing the fusiliers executing Fourie on that fateful Sunday. She was standing on the front stoep of their Pretoria house when the shots rang out. How deeply that sound imprinted on her heart for her youngest daughter to recount the story with such depth of emotion in later years.

The Boer Rebellion was finally brought to a halt by the Union Forces early in 1915. With the exception for Lt. Col. Maritz who fled to Angola and Europe, and Brig. Gen. Beyers who had drowned in the Vaal River, all the top rebel leaders were arrested along with many of their commandos and jailed. Their sentencing may have been influenced by a letter from Smuts’ old friend, Emily Hobhouse. Her heart still full of anguish for what our Boer women had suffered during the Boer War, and being something of a prophet about this World War, she had pleaded with Smuts about the rebel leaders on 29 October 1914: (Bold captions are mine)

Since the start of hostilities in 1914, German immigrants in the Union were considered “enemy aliens” and thousands of men were interned in “refugee camps” all over the country. Women and children were generally exempted, but those deported from sub-Saharan enemy territories such as South West Africa and the Belgium Congo were not. One such interment camp was located at the Roberts’ Heights military barracks outside Pretoria, where the interneé Hans Ette, a farmer from Natal, described the camp conditions as “good, water better than Johbg, plenty of space, only the food was awful and wholly insufficient.” Legal secretary Hertha Brodersen Manns was deported along with all the residents from Lüderitzbucht and interned in the Roberts Heights camp. Families lived in one compound, single women and men in separate compounds. (In 1939 Roberts Heights was renamed Voortrekkerhoogte. This is also where my husband did his basic military training in 1980 before being stationed at Wynberg Military Hospital for the then-compulsory two-year military service in South Africa.)

This is then where Ouma Hannie Lampen and four other women were heading on 26 May, 1915. They were given a Martial Law pass for their visit, but we can only speculate what they were doing there. The general public in South Africa was not particularly friendly to Germans after news came of a German submarine attack on the ocean liner Lusitania in that same month. Mobs had rioted and looted German homes and businesses in Johannesburg and elsewhere, although I would imagine the mood in Pretoria to have been a bit more split between pro- and anti-German sentiment? In fact, rumors that the Boer rebels were indeed planning a mutiny to free internees at Roberts Heights prompted the closure of this camp just after Ouma’s visit in May, and the transfer of internees to Fort Napier in Pietermaritzburg. The dates make me wonder, were Ouma and the other women there on a Samaritan’s mission or were they part of something else?

In August 1915 seven thousand Afrikaner women marched from Kerkplein in Pretoria to the Union Buildings with petitions, letters and telegrams from women all over South Africa to Defense Minister Jan Smuts, demanding an end to South Africa’s participation in the war and for the rebel leaders be freed. According to Ouma Hannie, who was part of this march, Smuts refused to see them and instead sent a deputy to meet with the women. To the women this was the ultimate betrayal by a “traitor and a coward.” Henceforth the Lampen kids (subsequently extended to my siblings and me too!) would, under no circumstances, be allowed to go near Smuts’ farm in Irene—very close to where I grew up. The farm held a sort of mystique to me during my childhood… It is, in fact, a beautiful place, of which Emily Hobhouse had written in 1912, “I am glad Irene remains a joy to you, an increasing joy, and I hope the farm begins to pay. At least it makes Mrs Smuts very happy and the children healthier than they could be in Pretoria…“

By the end of 1915 most of the 239 convicted rank and file rebel prisoners were released. Gen. de Wet was sentenced to six years but served only six months. Other leaders were released in 1916. The South African Defense Forces continued fighting in German South West Africa, Belgium and France. Delville Wood, the Somme, Ypres are but a few places where South Africans sacrificed their lives. Not widely known is that many black South Africans also served in the Armed Forces—albeit in much less “honorable roles”, clearing the battlefields of the dead and digging trenches. Many died in 1917 in a naval collision on the British troopship SS Mendi in 1917, the year that Jan Smuts was invited to London to become part of the British Imperial War Cabinet. Smuts is accredited with being the founder of the Royal Air Force—in which our cousin Sailor Malan flew during the Second World War.

On November 11, 1918, Germany’s Keiser Wilhelm II abdicated. World War I ended. At the Paris Peace Conference Jan Smuts was the only delegate to denounce the conditions of surrender imposed on Germany, predicting that Germany’s humiliation would lead to more trouble.

Over the next few decades four empires would disintegrate, WWII and numerous smaller wars would rage into our lives. The Lampens continued to build their lives in a bitterly divided South Africa. An English woman had foreseen the bitter results on the Afrikaner nation, an Afrikaner would foresee the world wide crises erupting through both World Wars.

After Louis Botha’s death in 1919, Jan Smuts became the Prime Minister of South Africa until Hertzog’s Afrikaner National Party election victory in 1924. He served South Africa again as PM between 1939 until 1948. Emily Hobhouse’s “Oom Jannie” would become Field Marshall Jan Smuts in the British Army in 1941, also serving in Churchill’s WWII Imperial War Cabinet. Jan Smuts was the only signatory to both the peace treaties that ended WWI and WWII. A brilliant statesman equaled only by his very good friend, Winston Churchill, Jan Smuts was regarded by Ouma and Oupa Lampen as a bitter enemy.

Incidentally, during the Anglo Boer War (1899–1902) it was then-State Attorney Jan Smuts who had issued the arrest warrant for the British journalist Winston Churchill (Lampen Post #23A.) Meeting up with Smuts again in 1917, Churchill remembered this incident, “I was wet and draggle-tailed. He was examining me on the part I had played in the affair of the armoured train—a difficult moment.” The two future world leaders would become the best of friends during the next few decades. As a statesman, Churchill thought Smuts was “as I imagine Socrates might have been.” Smuts’ influence was so strong on his friend that Churchill’s doctor felt that “Smuts is the only man who has any influence with the PM; indeed, he is the only ally I have in pressing counsels of common sense on the PM…” About their friendship, Churchill wrote in 1945, “Smuts and I are like two old love-birds moulting together on a perch, but still able to peck.” – Great Contemporaries, Paul H. Courtenay.

After the death of Jan Smuts in 1950, Churchill said, “[We] who are left behind to face the unending problems and perils of human existence feel an overpowering sense of impoverishment and irreparable loss.“

Resources:

• World War I “…was a global war originating in Europe that lasted from 28 July 1914 to 11 November 1918… [It] led to the mobilization of more than 70 million military personnel,

including 60 million Europeans, making it one of the largest wars in history. An estimated nine million combatants and seven million civilians died as a direct result of the war, while it

is also considered a contributory factor in a number of genocides and the 1918 influenza epidemic, which caused between 50 and 100 million deaths worldwide. Military losses were

exacerbated by new technological and industrial developments and the tactical stalemate caused by grueling trench warfare. It was one of the deadliest conflicts in history and

precipitated major political changes, including the Revolutions of 1917–1923, in many of the nations involved. Unresolved rivalries at the end of the conflict contributed to the start of

the Second World War about twenty years later.”

• “In the spring of 1915, shortly after losing a friend in Ypres, a Canadian doctor, Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae was inspired by the sight of poppies growing in battle-scarred fields to

write a now famous poem called ‘In Flanders Fields’. After the First World War, the poppy was adopted as a symbol of Remembrance.” – British Legion Story of the Poppy

• Emily Hobhouse, British heroine of the Boer people for her stalwart opposition to the British concentration camps established in order to bring the rebel Boere to heel.

• List of Governor-Generals of South Africa 1910–1961

• Churchill, Winston: Great Contemporaries: “The three most famous generals I have known in my life won no great battles over a foreign foe. Yet their names, which all begin with a

‘B’, are household words. They are General Booth [founder of the Salvation Army], General Botha and General Baden-Powell…”

• https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jan_Smuts#Soldier,_statesman,_and_scholar

• The Most Violent Century – Stephen Elliott

• At Cambridge, Jan Smuts was awarded. among many prizes and accolades, the coveted George Long prize in Roman Law and Jurisprudence. About Smuts’ legal studies, his tutor,

Professor Maitland—”the modern father of English legal history”, described Smuts as “the most brilliant student he had ever met…” – Wikipedia: Jan Smuts

• https://epdf.tips/selections-from-the-smuts-papers-volume-3-june-1910-november-1918.html

• https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Koos_de_la_Rey

• https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maritz_rebellion

• Jan Smuts and the Old Boers

• http://samilitaryhistory.org/vol143rm.html – from The diary of Dr Charles Molteno Murray in the Boer Rebellion of 1914

• Jopie Fourie execution letter

• https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/union_of_south_africa

• Civilian internment in South Africa during World War – Hans Ette comments.

• P.O.W. and internees in South Africa – closure of Roberts Heights

• Lampen Family Post #23,A What About the Men, stories about the Anglo Boer War

• Jan Smuts Founder of Royal Air Force

• https://winstonchurchill.hillsdale.edu/jan-smuts-churchills-great-contemporary/