Jan Heijstek new life in South Africa

Most of the story this week comes from the autobiography that our Oupa-grootjie Jan Heystek wrote in 1926.

Our timeline moves to 12 April 1863 in the Boer Republic of Transvaal, where it was time for the Heijsteks to start a new life beyond the little two-rooFm home provided by the Rev. Postma. They had survived a fairly traumatic year since they left Giessen in Noord-Brabant, the Netherlands. Jan (snr.) had lost his beloved Johanna nine months earlier on board the Willem Hendrik. The five boys must have grown up pretty fast during this year, and little Elizabeth was now five years old, needing a mommy herself. On this day, forty-seven year old Jan Heijstek got married to his second wife, twenty-three year old Hester Maria du Plessis. A week or so later the family moved to a piece of farm land given to Jan by a certain Johannes Venter. Originally named Waterval (no.4) and a bit later renamed Arnoldistad, the land was situated right next to the Hex River. This is now in the Transvaal (not the well-known Cape Hex River valley), near the present-day Kroondal area, as far as I can track the location. At this point we lose all new information about Jan and Johanna’s little Elizabeth. It is assumed she died in childhood on this Arnoldistad land. The youngest surviving son on the journey to South Africa, Pieter, lived until 1883, when he died at 31 years old without getting married. Another six sons were born to Jan and Hester between 1864 and 1877. Adding the four sons from Giessen and six sons from South Africa who all got married and had children, our Heystek clan in South Africa expanded quite a bit. In fact, Jan had eighty-two grandchildren! Now start a South African Heystek-family tree with that, and it is no wonder we have all lost contact with one another, all those hundreds of cousins in South Africa alone. ‘Anyone up for a family-gathering?

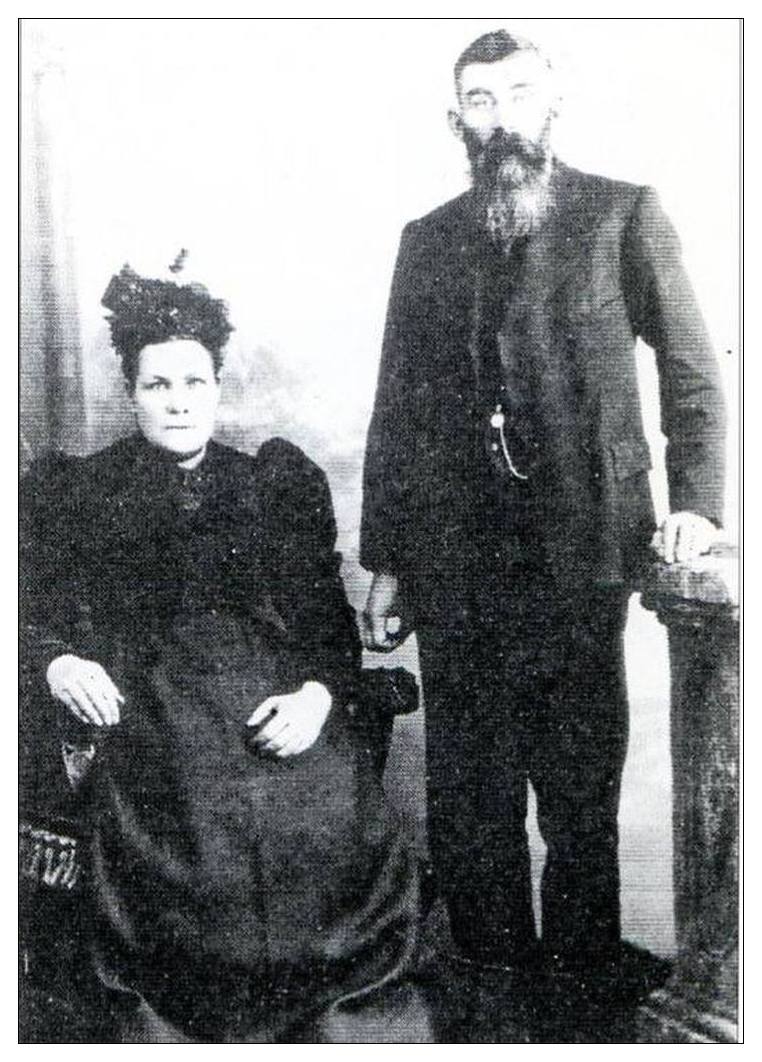

Groot-oupa Jan Heystek, 1848-1932

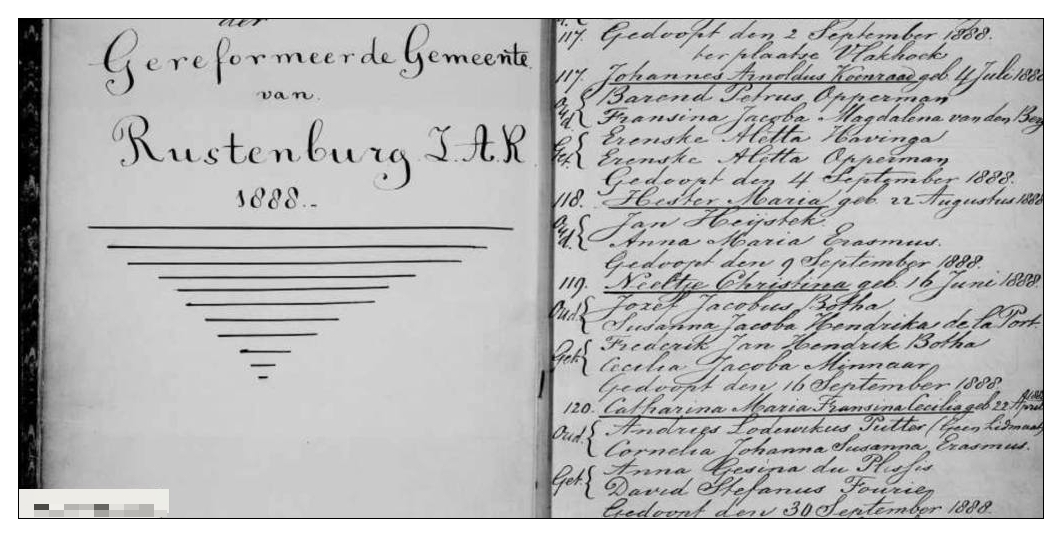

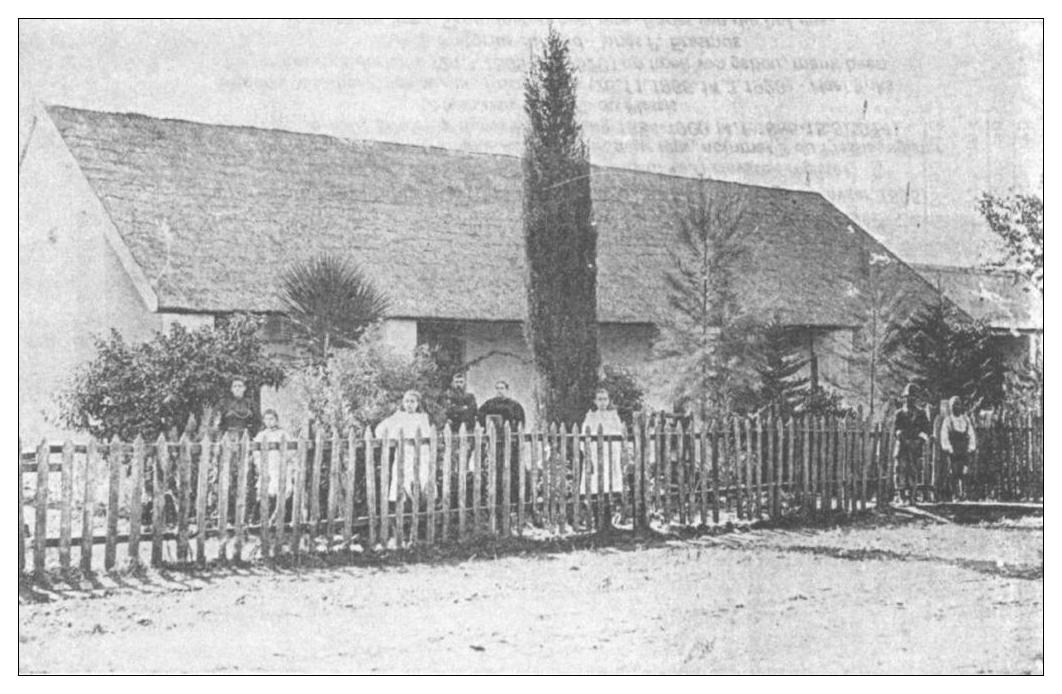

Christening of the youngest daughter, Hester Maria, in 1888 at the Rustenburg Reformed Church. (Middle of the page)

By end of 1863, Jan (snr.) was asked to join the civil war between the Kruger and the Pretorius parties. Fortunately, after some bluster this way and that, Jan (snr.) did not see any action and the hot-head-butting Afrikaner leaders finally decided to give it a rest in January of 1864. Marthinus Wessel Pretorius regained the presidency in the Transvaal Republic and Paul Kruger became his Commandant-General. Ja-wat, nê. In April 1864 Paul Kruger bought the Waterval property where Jan lived, and where his son, Jan (jnr.), our now-sixteen year old Oupa-grootjie, started teaching school to the ten children of Paul Kruger’s brother, Tjaard Kruger, with a salary of £3 a month, free lodging and a small piece of land to grow tobacco.

First public auction of sugar in Ladysmith, Natal, c 1870.

This would have been similar to what Jan Heystek experienced while selling his tobacco

Young Jan now also became a “burger op de Veldcornets lijst” – ready to be called up in case of war. His first taste of hostilities happened the very next year in May of 1865, during the Second Free State-Basotho War. However, the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (Transvaal) was not part of this war, so his involvement was quite by chance. Jan had a load of tobacco to sell, and got permission to travel with the Tjaard Kruger/Hans Botha party (also selling tobacco) to Pietermaritzburg. After they sold their wares in Ladysmith and had just started on their way back, they encountered a large group of armed Sothos who had crossed the Drakensberge over into Natal on horseback in search of cattle to raid. Jan simply wrote in his autobiography that they were robbed and “door Gods genade er nauwelijks met ons leven uitgekomen zijn”. (Through God’s mercy we narrowly escaped with our lives). Other travelers from the Transvaal, however, got killed. In 1931 The newspaper, “Ons Vaderland”, published an article about Jan’s life that gives more detail on that attack: “… they were also beaten with knobkieries until one of the [Sotho] leaders found out that they were Transvalers, [he] took a cattle sjambok and whipped all the [Sothos] back all the while yelling that they have no war with Kruger’s people…” Apparently Jan, Tjaard and Hans spent that night hiding under a cliff with nothing but the shirts on their backs. The next day a Free State patrol rescued them, retrieved their wagons and provided them with fresh oxen to get back home again. For a young Dutch immigrant this must have been a frightening ordeal. (See the link in resources for the full scope of this war.)

The Krugers must have been happy with Jan’s teaching skills, as yet another Kruger cousin asked Jan to teach his kids for the next year on the farm Middelkraal. After that Jan was asked to manage a school of twenty children on Daniel Elardus Erasmus’ farm, Waaikraal, near Sterkstroom. His salary was now such that until he got married, Jan could give half of his income to his father, Jan (snr.), as a thank-you for all his father had invested in his life. All through Jan’s story one reads about his heart for his family.

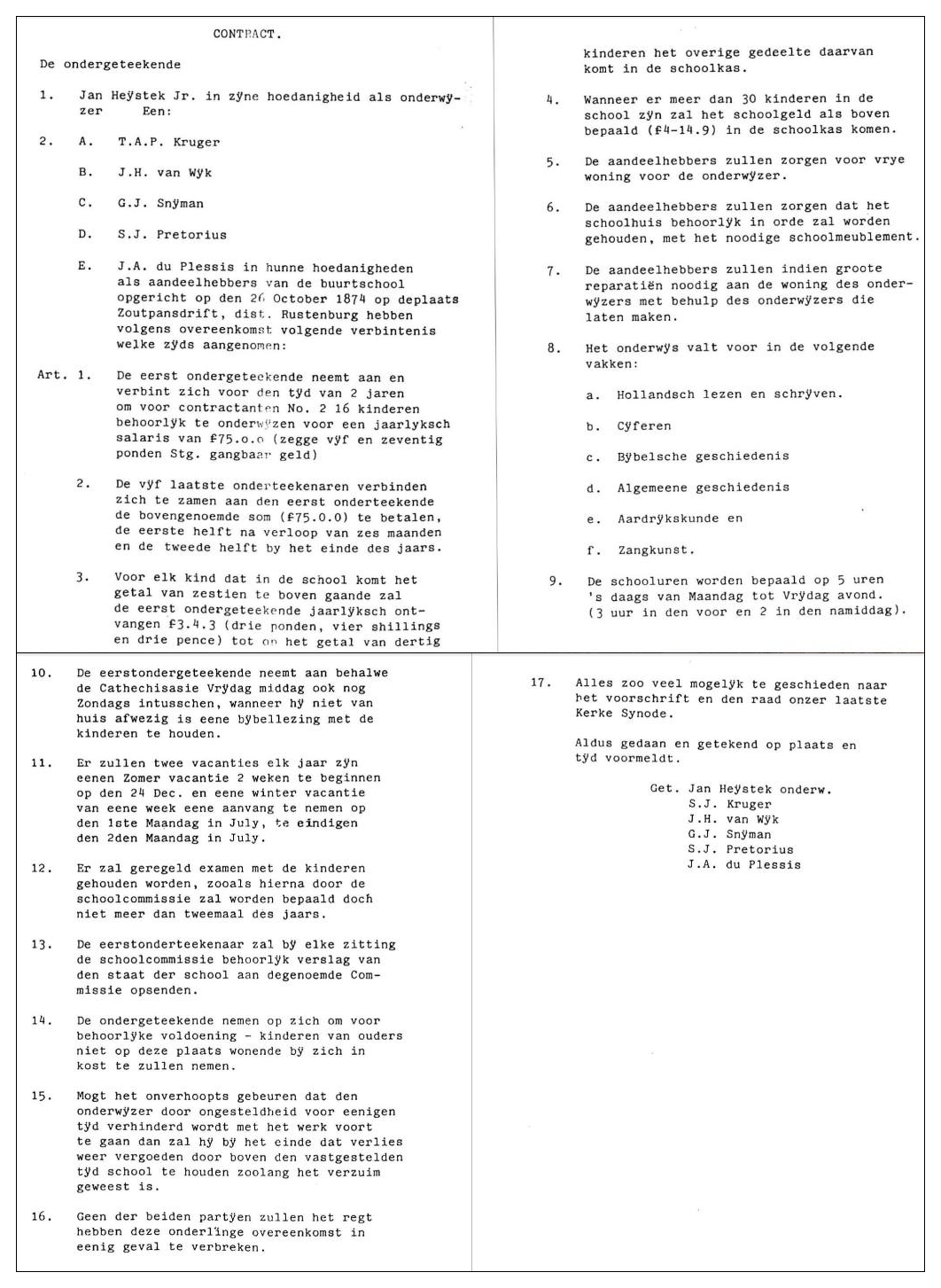

Jan’s first teaching contract

Now this Meneer Erasmus had a certain lovely daughter… and on April 20, 1868, Jan and his beloved Anna Maria Erasmus got married. Anna Maria’s mother, our 2nd-great-grandmother, was Helena Catharina Malan, sister to the Hercules Phillipus Malan that I wrote about in the May 5, 10 and 11 posts. There was reason for Jan to be quite in awe of his new mother-in-law… but that is a long story for another time. Not long after their marriage, Hercules in fact requested Jan’s teaching services on his farm, Rincojaalskraal. Is rincojaals the old word for the “rinkhals” snake (ring-necked spitting cobra)? Oy, he must have had quite something happen there for such a name!

Scarcely a month after his wedding with Anna Maria, Jan was called up for commando duty in a war against Mapela. Dryly he added that he did not request a stay of duty from the Transvaal Boer authorities on the grounds of the Biblical “laws of Moses” (giving a newly married man one year of time alone with his new wife before being called up into any wars)… At any rate, this commando duty took only 46 days, during which Jan, for the first time, saw the casualties of war on both sides.

Groot-oupa Jan Heystek and groot-ouma Anne Marie Erasmus

Back home Jan set himself to building his own clay house with three rooms, where he and Anna Maria lived until 1875. During this period Anna Maria gave birth to six children, including our Ouma Johanna Elizabeth Heystek-Lampen (1873). Two of the babies died in infancy. In 1875 Tjaard Kruger once again requested Jan’s teaching skills, so the family now moved to Zoutpansdrift, where Jan had a proper “neighborhood school” for about thirty pupils. He received £120 a year, including a decent home, ten acres of land on which to cultivate tobacco, wheat and mielies, keep milk cows, a team of oxen, and other livestock all being taken care of for him obviously by farm laborers working for Tjaard. This relative peace and prosperity lasted for a year until when the First Sekhukhune/Pedi Wars broke out in 1876 and Jan was commandeered along with all other available men. However, a family need now superceded this call to duty (fortunately the veldcornet in charge agreed) and Jan was given leave to tend to his 72-year old father-in-law Daniel Erasmus. The elderly Daniel had just sold his farm, Waaikraal, to the Hermansberg Missions Society in aid of the Bakwena-Bamagoepa tribe from Mamagalis, and was unable to move himself, his wife and their twelve-year old son to Leewfontein in the Elandsrivier area. Since Jan had just brought Anna Maria and the children over to Waaikraal to be safe, he now took charge of the move and resettlement while the two oldest Erasmus sons went and fought in the Pedi wars.

My word, these families moved a lot! Shortly after their arrival at Leewfontein, Daniel Erasmus bought the farm Klipfontein, selling Leewfontein to his two older sons. Jan and family again moved with Daniel so that Jan could care of his in-laws. In 1878 a devastating malaria epidemic broke out. In the ensuing months most of the people in this area got sick and many died—including both Anna Maria’s mother, Helena Erasmus (Malan), some of her Malan family, Helena’s husband Daniel Erasmus, Jan’s brother Joost’s wife, and many neighbors all around—this epidemic wreaked havoc on the families. The farm Klipfontein changed hands a couple of times and finally became the property of Jan Heystek, who bought it as an inheritance for his children. The area became known as Heystekrand, near Rustenburg.

Peaceful living in Rustenburg

In the meantime, for the past three years trouble had also been brewing outside of the Transvaal. Britain’s attempt to include the South African native tribes and both Boer republics (Transvaal and Orange Free State) in a “Policy of Confederation” à la Canada’s English and French provinces, was smacked down by the Boere during the previous year 1875. In 1877, the British Secretary for Native Affairs in Natal, Sir Theophilus Shepstone, simply annexed the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republic (Transvaal) for Britain. Just like that. The Transvaal Boere dared not react, as the Zulu King Cetshwayo and the British in Natal were still on good footing with one another, and Cetshwayo had been building his army up using many of the old King Shaka’s fearsome military practices, now including modern weapons. There were enough uprisings and skirmishes all around the Boere for them not antagonize another potential enemy to their east. Instead, Paul Kruger (now vice-president of the Z.A.R.) travelled to London twice to appeal, unsuccessfully, to the British government against this annexation of their republic. Shepstone, now the British administrator of the Transvaal, saw the Zulus creating “outrageous” conflicts on both sides of the Natal/Transvaal border, adding to the tinderbox of resentments building up among all the nations inside this unstable bit republic. Cetshwayo was found to be in “a defiant mood.”

Still, Britain was quite reluctant to start yet another colonial war. Eastern Europe was at a critical turning point and the empire’s interests there were at stake. They were already involved in the Second Anglo-Afghan War after unsuccessfully trying to annex that land in an attempt to prevent Russia from invading India, where Queen Victoria had just been proclaimed “Empress of India”. (What a mess!) Even Paul Kruger warned the Brits against warring against the Zulus, whose battle strengths he knew from personal experience during the Groot Trek. However, an arrogant and unwise challenge to Cetshwayo by the new British High Commissioner to South Africa in 1879, Sir Bartle Frere, finally opened up the first bloody chapter of the Anglo-Zulu Wars in January, 1879. Even though Britain secured final victory over the Zulus in 1883, continued hostilities only petered out in 1889 with Cetshwayo’s son Dinizulu being sent to St. Helena for treason. Napoleon’s banishment-island saw some interesting faces. Most of us probably have heard something or seen the movies about the worst battles at Isandlwana (Zulu victory) and Rorke’s Drift (miraculous Zulu defeat/English escape at a missionary station), but did you know that Piet Uys, younger son of the Voortrekker Piet Uys who was killed in at Italeni after he tried to rescue men who had ridden into in a Zulu trap, was killed similarly while fighting on the British side with Evelyn Wood and Redvers Buller? Wood’s mounted volunteers had ridden into a trap set by the Zulus at Hlobane Mountain.

Instead of British authorities instilling confidence in their “confederation” of British territories, as was actually intended, the Transvaal Boere reacted with a growing nationalism after some of their leaders were arrested for “anti-British statements”, and a farmer was wounded in November 1880, when the Brits tried to auction off Piet Bezuidenhout’s ox wagon after he refused to pay tax on it. You don’t mess with a Boer’s ox wagon! Armed Boere intervened, shots were fired, the wagon was reclaimed, you can well imagine the scene.

The fuse for the “Eerste Vryheids Oorlog” or First Anglo-Boer War, was officially lit on—of all dates—December 16, 1880, with the hoisting of the Vierkleur flag at Heidelberg, and a proclamation of war sent to the Pretoria (English) government. Oupa-grootjie Jan had some strong opinions about the years of begging “alsjeblief mijnheer” (please, sir) to London, and was relieved that they now “took up the sword” to fight for their freedom. All burghers rallied to the fight, except those on border areas who had to stay and keep things safe. Which meant that Jan’s Klipfontein farm was in the crosshairs of potential tribal attacks, so he packed his family up and took them to Sterkfontein, leaving the farm and livestock in the hands of his staff.

Rustenburg saw a contingent of “Rooibaatjes” encamped outside the dorp, but skirmishes only took place from inside the camp towards town and vice versa. Jan himself was appointed “adjudant” over twelve men, riding patrol around the British camp, especially at night. He also kept an eye on local residents in the Hexrivier area, and caught a chap named Comson smuggling weapons to the tribes. And then of course, Hercules Phillipus Malan, whom we got to know through the Jameson Raid and talks with Khama, was a commandant in the war.

This incredible war that Britain lost so humiliatingly to a small group of Boere lasted just short of four months. Names like Bronkhorstspruit, Schuinshoogte, Laingsnek and especially Majuba Hill, cannot be erased from the annals of Britain’s military blunders. “Some historians point to this humiliation as the very point marking the beginning of the decline of the British Empire.” – quoted from the tongue-in-cheek short video on https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gle6XyA_l9c. At least, the music is kind-of cheeky.

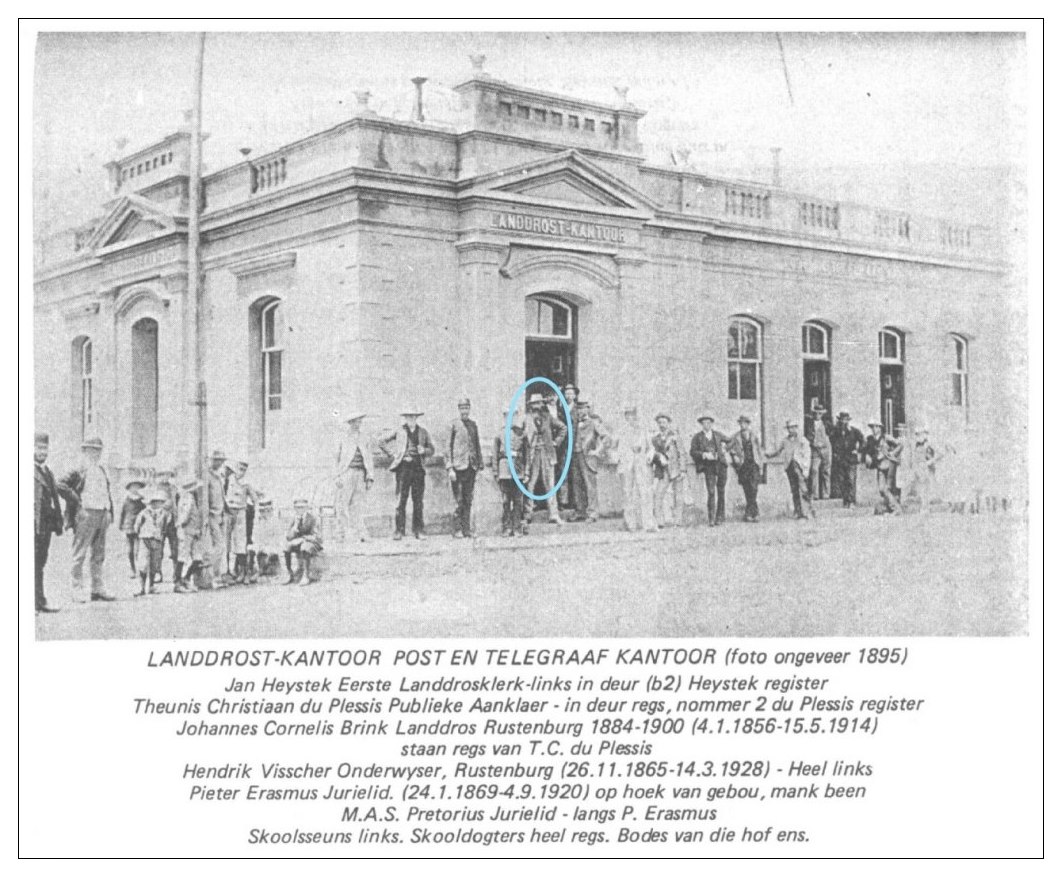

Taken from the Heystek Familieboek Jan Heystek, first Landdrostklerk (circled, check his confident stand!), c. 1895.

This Landdrost office is the same building where Oum

Majuba was the turning point in this disaster for the English, and truce was declared on 6 March, 1881. Jan returned to his family and started farming again. A year later Hercules Malan asked him to take on the administrative post of “Klerk en Sekretaris” at the “Kommisaris van Naturellen en Kommandant, Pilanesberg.” He held this post until May, 1889, resigned and was immediately asked by Landdrost Brink in Rustenburg to become his clerk. The job description included “Landdrost clerk, prosecutor, justice of the peace, acting landdrost” (when Brink was out of town) and “zegel-en magazijnmeester”. So for the next nine years Jan, Anna Maria and the girls still at home enjoyed a peaceful life in Rustenburg. You may remember Ouma Hannie’s sister Emmie talking about the kids taking butter over to old Landdrost Brink’s house.

I hope to finish the last years of Jan’s life with a much shorter story in the next soon. It is tough to read so much of what he wrote and have to decide what to leave out!

Previously published on: https://www.facebook.com/groups/Lampens/

Resources:

•https://www.dropbox.com/…/Jan%20Heijstek%20zijn%20levensver… : Jan Heystek autobiography.

•https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transvaal_Civil_War

•http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/war/basotho.htm – Basotho Wars.

•http://dl.yazdanpress.ir/…/A_Military_History_of_South_Afri… – First Pedi Wars, p. 50–54

•https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Boer_War Zulu unrest, British Annexation, First Boer War.

•https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_Afghan_history

•http://www.britishbattles.com/zulu-war/battle-of-isandlwana/ and Rorke’s: Drift Anglo-Zulu Wars.

•http://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/s/idrqi8 1851 map of Natal and Zululand.

•http://www.sahistory.org.za/artic…/anglo-zulu-wars-1879-1896